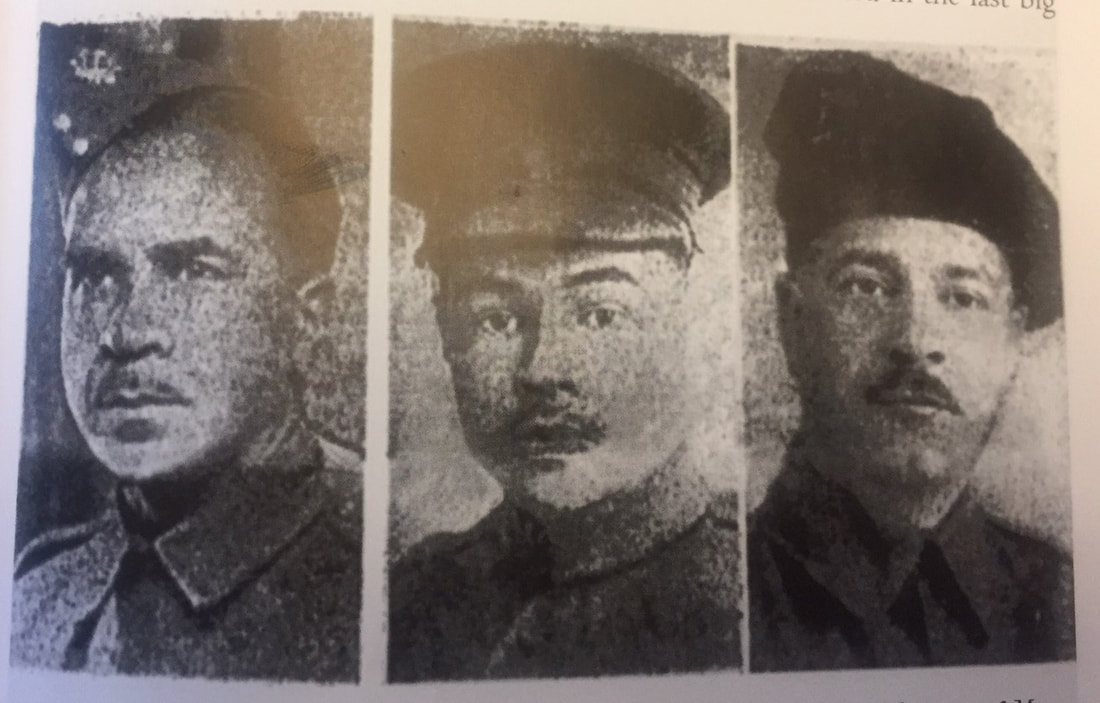

The Marshall family from Woodstock were well known as the four Marshall brothers all served in the armed forces. According to the book A Safe Haven, the Marshall family first appeared in Oxford County census in 1881 in Blenheim Township where the widow Eliza Marshall lived with her eldest son Thomas and his family. Eliza's two other sons, Horace and John moved to Woodstock in 1891 their older brother Thomas followed in 1901.

Horace and his wife Jane came to Woodstock in 1890 where all five of their sons were born: Harold, Wallace, Horace, Arthur and George. They all attended public school in Woodstock and Wallace went to Woodstock Collegiate (WCI). George died at 17 years of age. Growing up they all had jobs in Woodstock. Both Horace and Wallace worked for the Thomas Organ Company. However, the four remaining Marshall brothers moved to Toronto to find employment.

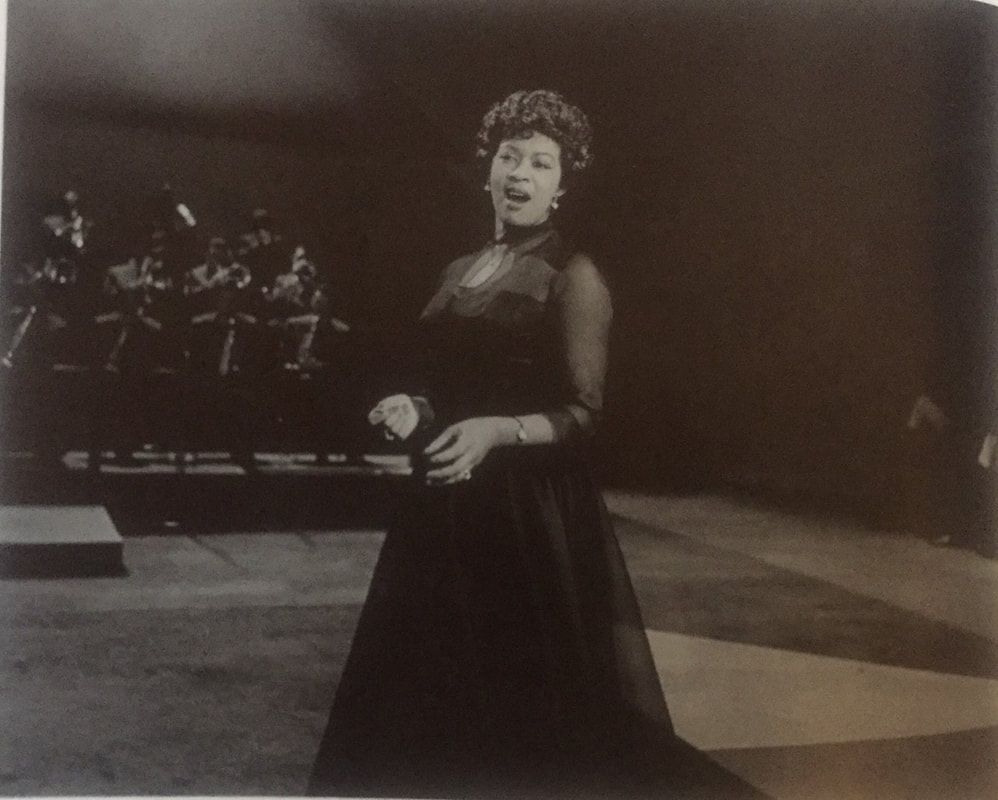

Phyllis made her debut at the age of 15 as a singer on CRCT and CBC radio stations. During the 1940s she sang blues and jazz with various Toronto dance bands. During 1947 to 1948, she toured throughout the United States with the Cab Calloway Orchestra. Phyllis appeared on a CBC radio show “Blues for Friday” from 1949 to 1952. In the 1950s she starred in two television shows: “The Big Review” 1952 to 1954 and “Cross Canada Hit Parade” from 1956 to 1959. She also performed with the great Canadian jazz pianist the late Oscar Peterson on BBC-TV.

One of Phyllis’ last performances was for Nelson Mandela’s 70th Birthday Tribute at the Freedom Fest in Harbourfront in 1988. Phyllis Marshall died in Toronto on February 2, 1996. She is remembered as one of Canada’s pioneer Black television super star.

For forty years, Henry Morton worked at the McIntosh Coal Company. His first wife, Hattie died in 1906. He then married Annie Lewis in 1918. The couple had ten children: six sons Harold, Donald, McKenzie, Embry, John and Douglas; and four daughters: Dorothy (husband John James), Isobel (Allan Bennett), Elizabeth and Phyllis. Henry and Annie were married for 36 years when Henry died in 1954 at 81 years old.

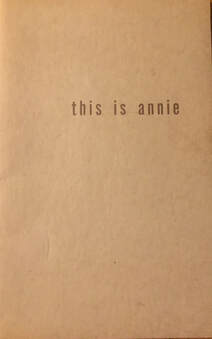

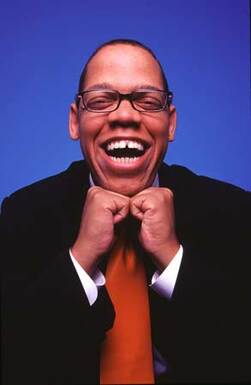

After Henry’s death, Annie married jack Walters. In 1965 she published a book of seventy poems entitled This is Annie. By then she was a paraplegic. Annie died in 1967 at 68. Annie’s children Isobel, Don and Douglas remained in Woodstock. Douglas Morton was married to Ida nee Lawson and they have two children: Greg, the famous entertainer, married to Debra and Nanette who is married to Mark. After 55 years of marriage, Douglas died on November 22, 2010.

Greg Morton appeared as a contestant on Season 14 of America’s Got Talent on May 28, 2019 where he impressed the judges that Howie Mandel promised to invite Greg to open for him. On the show Greg performed his famous two-minute rendition of the Star Wars Trilogy that had the audience of all ages in stitches. At 61 Greg Morton has achieved success that will continue. Greg Morton may even get a street named in his honour right here in Woodstock, Ontario.

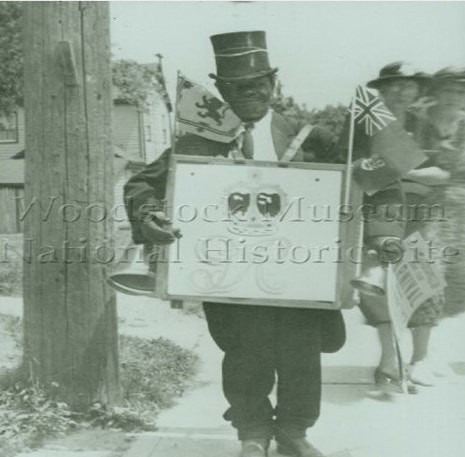

Woodstock residents nicknamed him George “Washington Jones” a name he did not like but one that stuck and has since been immortalized. For twenty-five years George Gravy paraded around the streets in Woodstock advertising everything from hockey and baseball games to local events like dances, the Lion’s carnival, Woodstock Fair and the Rotary Bingo. Many of the Woodstock merchants hired George to advertise their products and services.

With failing eyesight, George Gravy would be seen around town tapping his way with his white cane. Many prominent citizens would help him across the street. On December 8, 1951, George Gravy died at the House of Refuge and was buried in the Baptist Cemetery in Woodstock. Famous businessmen were his pallbearers. In 1952, the late Percy Canfield took up a collection and erected a granite headstone that read “George Jones, 1856-1951, Town Crier”.

As illustrated, these are but a few of Woodstock’s Black residents who have been a part of history in Oxford County for over 150 years. These earlier settlers have and continue to contribute to their communities.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed