Both women were surprised but pleased by the large turnout for the protest. They were also contacted by Woodstock Police Chief Daryl Longworth who wanted to begin conversations and they now sit on a new advisory board to address diverse cultures.

Like the United States, Woodstock and Oxford County, Black people have been a part of history for quite some time. Like many parts of Canada, Oxford County was home to a number of Black communities that have since disappeared and are largely forgotten. Few monuments commemorate these long-gone hamlets neither of early Black settlers nor of the individuals who made contributions to Oxford County.

The late Mary Evans-Smith volunteered at the Oxford Historical Society who dedicated her time researching Black history in Oxford County during the 1990s. She believed if you “talk about Canada being a multicultural country, every race and colour must be included in its history.” Otterville historian, Joyce Pettigrew, documented local Black settlements in her 2006 book, A Safe Haven The Story of the Black Settlers of Oxford County. Although limited compared to other communities throughout Oxford County, Woodstock does have a rich Black history in both people and buildings that the scope of this four-part blog post will address.

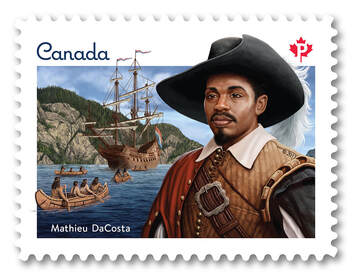

However, to understand how and why Black people came to Oxford County, we must know the history of Canada, one which and to some extent, is still not taught in school. Forgotten in our history books is the mention that slavery existed Canada. Black people first arrived in Canada as slaves by the British around 1608. But the first recorded Black person to arrive on Canadian soil was Mathieu da Costa from Azores. He was not a slave but a linguist, an explorer, a pioneer and a translator between the Micmac Indians and the French explorer with Samuel de Chaplain in 1606.

Olivier Le Jeune, a boy from Madagascar, was the first recorded slave that came directly from Africa and sold in New France in 1628. Captured in Africa at 6 years old, Le Jeune was transported to Canada by David Kirke. When Kirke left in 1629, Olivier was sold to a Canadian. He was baptized in 1633 and given the last name of one of the priest, Jesuit Father Paul Le Jeune. Oliver Le Jeune died in 1654 in New France.

In 1685, The Code Noir or “Black Code” became law which provided guidelines on the sale of slaves, their religious instructions and training, and the disposition of their offspring. Although referred to as “servants” rather than slaves, both Indians and Blacks were deemed to be property by their masters and were sold. French settlers preferred Indian slaves or panis. The majority of Indian slaves were Pawnees or from closely related tribes. The English settlers chose and brought Black slaves.

The slave population increased rapidly in Canada after 1783, when the United Empire Loyalist migrated from the United States to Canada after the Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1783. About 40,000 Loyalists found refuge in the British provinces of Nova Scotia, Quebec and later made their ways to other areas: like Kingston, York, Toronto, Newark, Niagara-on-the-Lake and Amherstburg. Along with these early Loyalists were Black soldiers who volunteered to serve with the British forces during the war. However, aside from Black Loyalists, some Loyalists brought over their slaves to Canada who would later see an end to slavery.

On June 19, 1793, Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe introduced a bill prohibiting the import of slaves into Upper Canada (Ontario). However, known as the “Slave Bill” faced great opposition but once passed, Upper Canada became the only British Colony to legislate for the abolition of slavery. This bill prohibited further entry of slaves into the province. Slaves already living in Upper Canada remained slaves for life, their children, born after 1793, could be free at age 25 and their children would be free at birth. It took another 41 years to abolish slavery throughout Canada.

On August 1, 1834, about 781,000 slaves were emancipated throughout British North America by the British Imperial Act. On that day, known as Emancipation Day, a slow exodus of Black people began from United States into Canada. Emancipation Day celebrations occurred in Woodstock and Ingersoll. In Natasha Henry’s book Emancipation Day, Woodstock hosted an event in 1898 that was advertised in the Daily Sentinel Review on July 22, 1898.

Between 1840 and 1850, there was a huge influx of Black people exiting the United States due to the passing of The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. (This act was a much stronger act than the earlier Fugitive Slave Law of 1793.) This law allowed slave owners to recapture runaways and even free Blacks, in northern Free states.

For many slaves, Canada represented a dream of freedom where slave catchers and lynch mobs couldn’t hurt them. Slaves on the Underground Railroad endured months and even years, of living like fugitives while bounty hunters and racist government policies were always trying to impede their flight to freedom. Most slaves started out their journey on the Underground Railroad by running away from their plantation in the middle of the night. Often the runaway slave was alone, but on many occasions whole families would escape together. Many Black people followed the North Star to Canada and some came to Oxford County via the Underground Railroad.

The Underground Railroad (also called the “Liberty Line”) was not underground nor did it have tracks but was a movement consisting of network of escape routes. The Underground Railroad emerged as a result of over 415 years of slavery in the United States that started in 1450 and continued through the Civil War until the passing of the 13th Amendment which abolished slavery in 1865. Oppressed slaves wanted a way out and with the help of Abolitionist and other Anti-Slavery advocates, many slaves escaped to freedom in Canada by following the North Star via the Underground Railroad. Slaves not only escaped to Canada but also to Mexico and the Caribbean.

With the advent of the steam railway, terms like the “Underground Railroad” were used as code words. The “train” would occasionally be nicknamed the “Gospel Train”. “Conductors” consisted of people or groups of people like the Quakers, freed Blacks, Sympathetic Whites, Native Americans, German farmers and various religious groups, who feed, clothed and hid escaping slaves from one point to another until freedom was reached. “Stations” were places the abolitionists hid their “cargo” - escaping slaves - like barns, churches, attics, cellars farmhouses or secret passages. The Underground Railroad began in the 1780s by the Quakers.

The relationship between Blacks and Quakers goes a long way and it is a close relationship. Quakers or - the Society of Friends - were the backbone of the abolitionist and anti-slavery movements. Being peaceful people, Quakers do not believe in violence and they also believe that all men are created equal and had concerns for social reform and education. The origins of the Quaker testimony against slavery and the slave trade can be traced back to George Fox, the founder of Society of Friends also known as the Father of Quakerism. He first spoke out against slavery in 1657.

Quote: "...no man can tell the intense agony which is felt by the slave when wavering on the point of making his escape....The life which he has, may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks, may be gained." ~ Frederick Douglass ~

RSS Feed

RSS Feed